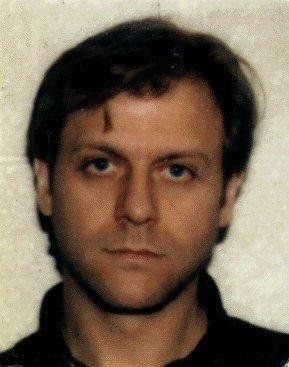

Michael Rectenwald smiles as we walk past glass walls with reflections of us walking. It's been a lively day for the NYU professor, writer and former Libertarian Communist. He arrived at Mercury Studios this morning, then spent two hours talking with Glenn Beck about academia and God for Glenn's weekend podcast. He's satisfied and hungry and a little cold — temperature-wise. I tell him the studio is always this cold because the stage-lights get so hot, and people wear sweaters year-round. So when we step out into the Texas heat, the sunlight is blinding like a warm hallucination.

We stomp through witchgrass and overgrown clover, then jaywalk across Royal Lane through tufts of exhaust from passing motorcycles. There are cars at every gas pump of the 7-Eleven, and the air undulates with gasoline fumes. This is one of those moments for Rectenwald — when the world is gliding along and you catch a glimpse of perfection.

On a sunny day like this, with everything so alive, you never expect tragedy. But it happens. Life is full of broken things, and sometimes you are one of them.

For now, Rectenwald is elated. He has the broad gait of a professor who's always chatting with students as he walks around campus. His accent hints at Pittsburgh abruptness, with the pace of a New York transplant, but he's also a lifelong reader, so there are refinements to his speech you hear mostly during sermons and lectures.

These are the last days of Texas summer. And Rectenwald is in a suit — looking rather professorial with his half-knotted tie and his hair mussed slightly. He has the added level of distinction you see in professors from elite universities. His glasses are Wayfarer-style, with those prescription lenses that get darker depending on how bright it is. At the moment, they are nothing but black.

We decide to have lunch at Desi District, an Indian restaurant next to the 7-Eleven. A bored family yawns at a brightly-lit table. It's not entirely clear that they're here for any reason. The room echoes with the jives and exotic tumbles of a Bollywood soundtrack — music that, however corny, somehow always sounds majestic.

None of the women at the counter understands a word that we say, and, to be fair, we cannot understand them either.

Point-and-order.

Smile and nod.

Nod, then pay.

I ask Rectenwald about the time he spent with Beat poet Allen Ginsberg.

“It was like a dream," he says. “It was like I was awake inside a dream."

At 19, Rectenwald sent Ginsberg a letter with five or six poems. Ginsberg replied, invited him to study at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

"Some conservatives on FrontPageMagazine.com," he says, then clears his throat. "Some conservatives said, about my book, 'We shouldn't be celebrating this book, this guy studied with Allen Ginsberg, a pedophile.'"

Rectenwald pauses. "For God's sake, I was 19 at the time." With a shrug, "[Ginsberg] never did anything to me. I don't know if he did anything to anybody."

He tells me about Billy Burroughs, son of Beatnik William Burroughs Sr., author of "Naked Lunch," a book about heroin and cockroaches and maybe pedophilia.

Burroughs Sr. killed his wife in a drunken game of William Tell. He was trying to shoot a highball glass off her head, but missed and shot her in the face. Rectenwald tells me that Billy was there that night and saw his mother die. A few years later, William Burroughs Sr. told a young Billy that, in order to be a great writer, he needed to have an “extreme experience:" He needed to do drugs. Billy accepted the advice.

Rectenwald recalls an occasion when Ginsberg left for a trip, and asked him to look after Billy.

“I was basically charged with being a babysitter, even though he was 33 and I was much younger than him," Rectenwald says. "His health was wrecked from speed, he was a speed addict, alcoholic, and he was definitely suffering from some mental illness."

Rectenwald has a poem titled, “Billy Burroughs Junior" in "Breach," his collected poems: “Staggering along a Boulder street, paranoid, / rejected, he curses the endless / progeny of a waitress in Tom's diner. / Carrying a six-pack of Colt Malt Liquor, spinning / cane and delusionary notion / of being in the wrong century; / 3 am, psychotic, arguing with himself, / advises me to 'sleep safely,' / Christian scripture at hear."

Not long after their time together, Billy died, drunk in a ditch by a highway.

We talk about drugs. Too many good ones die from drugs — now more than ever. Then we talk about LSD.

Acid is interesting, I say.

“Yeah, but it's also dangerous in a way," he replies. “People that have tenuous psychologies, they have to be careful because they could lose it and become psychotic."

I tell him my Uncle Mike's saying: “If you've got spiders in your head, acid is going to set those bastards loose."

“Absolutely," Rectenwald says.

* * *

The woman behind the counter calls out a version of my name. At least I think it's my name. It resembles my name only enough for me to feel lazy bewilderment. She repeats it a few times. I look around. She repeats. I look around. Eventually, we make eye contact and I lift myself out of the picnic-table seat, then pull two platters off the glass counter.

I tell Rectenwald that I enjoyed reading the literary parts of "Springtime for Snowflakes." When I finished it, I wanted to know more about who he was before his years of graduate and doctoral work, when theory took over.

“Absolutely," he says. “Theory took over. It killed my art almost entirely."

All the trouble began on Facebook.

In fall 2016, Rectenwald shared an article about this student. He found the kid clever. Immediately, friends and colleagues labeled Rectenwald transphobic. People he'd always gotten along with turned against him. He describes this as his “no more" moment. That night, he began posting satirical tweets under the handle @antipcNYUprof on Twitter.

Suddenly, the outrage was everywhere he looked, especially on campuses and among his fellow academics. In his memoir, Springtime for Snowflakes: 'Social Justice' and Its Postmodern Parentage, he describes the effect of this cultural shift. Isolated, alone, he doubted his politics. He could no longer call himself a communist, not without a community.

He writes in Springtime for Snowflakes:

As one Twitter troll put it: 'You're anti-P.C.? You must be a right- wing nut job.' But as I explained in numerous interviews and essays, I was not a Trump supporter; I was never a right-winger, or an alt-right-winger; I was never a conservative of any variety. Hell, I wasn't even a classical John Stuart Mill liberal. In fact, for several years, I had identified as a left or libertarian communist. My politics were to the left (and considerably critical of the authoritarianism) of Bolshevism! I had published essays in socialist journals on several topics, including analyses of identity politics, intersectionality theory, political economy, and the prospects for socialism in the context of transhumanism. I became a well-respected Marxist thinker and essayist. I had flirted with a Trotskyist sect, and later became affiliated with a loosely organized left or libertarian communist group.

His discontent grew. So did the cultural tensions toward discontent of his sort. When Hillary Clinton referred to Donald Trump supporters as a “basket of deplorables," Rectenwald felt disgust: His father had been an independent contractor, remodeling homes in Pittsburgh, a Reagan Democrat and father of nine; the kind of hard-working, blue-collar man that Clinton discarded as “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic, you name it." In defiance, Rectenwald became the “Deplorable NYU Prof."

His @antipcNYUprof Twitter account held nothing back. Here was an NYU professor excoriating NYU and professors and leftist ideologies — although, much of it also contains a conspiracy-minded paranoia that can be seen as a parody of the new far-right. He wrote about the deep state and red-pilling; he derided transgenderism, gender fluidity, socialism, Antifa.

Before long, the account caught people's attention. Nobody knew who was behind it. Was it actually an NYU professor? A writer with Washington Square News, NYU's student paper, sent the account a private message asking for an interview.

“Sure," Rectenwald replied. The article ran and, for the first time, Rectenwald linked himself publicly to the @antipcNYUprof Twitter handle. The backlash was immediate, and after that moment his life would never be the same.

* * *

Know that Rectenwald's @antipcNYUprof persona deals in verbal irony and wordplay. Even the title of "Springtime for Snowflakes;" it's a play on "Springtime for Hitler," the fictional musical from Mel Brooks' "The Producers." In it, "Springtime for Hitler" is described as "practically a love letter to Adolf Hitler," written by the character Franz Liebkind, a former Nazi and total lunatic who says things like, “Not many people know it, but the Fuhrer was a terrific dancer" and marches around his roof in Nazi regalia, sending messages via carrier pigeons to Argentina — you know, where all Nazi bigwigs hid out after the war.

What does it mean that Rectenwald changed “Hitler" to “Snowflakes"? The equivalency can't be accidental. And is it satire? The book doesn't read like satire, not the memoir portion of it, anyway. Although, at the back, he does include a selection of his most inflammatory tweets. And then there's the ending:

“So, while in this book I have used more measured and scholarly writing on the topic, my readers should not expect my Twitter or Facebook pronouncements to become less strident any time soon."

What does he mean by “measured and scholarly"?

I agree that the book is measured and scholarly, but it also has the word “snowflake" in its title. As noted on Urban Dictionary, the term is a pejorative applied to the political left, specifically to college professors and students with social justice leanings.

I wonder, is Rectenwald a satirist or a troll? Does this distinction matter anymore?

* * *

Overall, the political right has embraced Rectenwald, the same way they have with Dave Rubin, Christina Hoff Sommers, Jordan Peterson, Brett Weinstein, Joe Rogan, Cassie Jaye, and myriad other lifelong liberals who got kicked out of the tribe. As each of them knows, this sudden (and extremely public) ostracism leaves a person vulnerable. Occasionally, the "alt-right" sneaks in and takes advantage of that vulnerability. Rectenwald is self-aware. He sees the dangers of becoming a darling of the "alt-right."

“I think it's about who you are, it's not about where you appear," he tells me. “I would never go on a podcast with Richard Spencer, that's for damn sure — I don't know how that guy even lives. But I've been on some that people on the left would dub as 'alt-right.'"

Specifically, he appeared on Milo Yiannopoulos's podcast. Recently. After the left and the right deemed Yiannopoulos to be cancerous. An anti-truth provocateur. Up to no good. Out to bring chaos to a world already drowning in chaos and in need of an answer.

In the Q&A portion of "The Rubin Report," included in my profile of Dave Rubin, Rubin asked Ben Shapiro, “Any chance of a future discussion with Milo?"

“No," Shapiro replied. It got quiet for a moment. He took a drink of water, then said, “I'd rather talk with people that have something to say."

* * *

You can trace Yiannopoulos' “post-Truth" worldview and Machiavellian principles back to Saul Alinsky's "Rules for Radicals," a guidebook for political trolling, designed to teach Have-Nots how to overthrow their oppressors and take hold of power. Despite Alinsky's protestations, the book is Marxist, so it has traditionally remained a favorite of the far-left and a boogeyman of the right. Lately, as evinced by Yiannopoulos, the far-right have begun using it as well, and, depending who you ask, they've done so with great success.

Rule 5 of "Rules for Radicals" states that “Ridicule is man's most potent weapon. It is almost impossible to counterattack ridicule. Also, it infuriates the opposition, who then react to your advantage."

Elsewhere, Alinsky writes, “You can threaten the enemy and get away with it. You can insult and annoy him, but the one thing that is unforgivable and that is certain to get him to react is to laugh at him. This causes an irrational anger."

But just as much as there's a rise in Alinsky trolling, there's a satire revolution, devoted to meaningful change. Unlike the ugly-spirited bullying that Alinsky promoted, this satire is a legitimate instrument for social insight. In "A Conservative Walks Into a Bar: The Politics of Political Humor," Alison Dagnes writes, “When satire sheds light on a perceived injustice, it also references the justice that should be found instead."

Satire uses humor to highlight a cultural problem, making it a little softer, then asks us to look into the mirror. If we can laugh about it, there's a chance we can save ourselves.

So which is it? Is Rectenwald provoking chaos by any means necessary, at all costs, for selfish reasons? Or is he calling attention to a corrupt institution? Is he using ridicule for dubious reasons? Or is he bravely saying what many others are afraid to say? Is he a bully? Or is he fighting a bully?

* * *

The mystery plates of food keep arriving. We have gnawed intermittently at the tangled meal on our plates. Puttered the garlic nan into a crib of lame sauce.

“It's really tough," he says. “To make fiction work is so hard."

Rectenwald is literary. Really, it's his basis. In his short-story collection "The Thief," he mixes literary fiction with Charles Bukowski sharpness. He's a fiction writer and a professor. He brings both to bear in "Springtime for Snowflakes."

“It has a fast pace," he says, “like fiction — have you noticed that? It moves quickly."

The book has definite literary moments. Like this passage about Allen Ginsberg:

By the time I left Allen and his apartment, it was night. The stars illuminated the pastel adobe houses scattered across the Boulder mesa, which seemed to float beneath the westward mountain peaks and somehow reminded me of a desert and an ocean floor at once.

It also has academic passages:

The postmodern theoretical understanding of language as open-ended and opposed to the closure of 'totalizing' ideological systems explains postmodern politics. While postmodern theory does derive from the political left in France, it is definitely not Marxist.

He tells me that, of the two, he most enjoys the literary elements. In fact, he says, from the start, he saw the book as a literary performance that he would do once then never touch again.

“I really worked hard on the prose," he tells me. “Prose — the way words work — I'm really deeply into. That's what I'm most proud of about the book — the phrasing, the language, the writing itself, you know?" He pauses into a half-grin. “And I think — not that this is possible — I think I made postmodern theory almost comprehensible."

Then he kind of explains the joke, inadvertently adding a layer of postmodern refraction to the moment.

His eyes tilt as he tries to recall what we'd just been talking about: Trolls... Writing... Ah, the book.

“I tried really hard to crystalize things," he says, “and also not to belabor things. Just move on to something else. Just say it as clearly as possible. Then move on."

I say that he did a good job of that today in his interview with Glenn.

A flush of excitement spreads over his face.

“Oh, cool," he says, squirming a bit. “Man, that was fun. Wow. Intense, too. Yeah, that was intense. I loved it." He pauses. “That was definitely the best interview I've ever had."

You can feel this energy when you listen to the podcast. Especially the second section, which is raw with emotion. To begin with, the studio where Glen's Podcast is recorded always has a magical feel to it. Even more so for the podcast, with windshield-sized lights spidering down around a near-empty auditorium. Secretly, I enjoy seeing people's reactions to that studio. How they push through the swinging doors and suddenly it's like they're in a planetarium, with unherded stars all spread across the ceiling. Rectenwald was no exception. He looked everywhere for a moment, then made his way to the table. So much space. Three cameramen and a producer, and a couple of us perched on the stage out of frame. In the glare of lights, Rectenwald and Glenn talked about life at a table at the heart of a 10,000 square-foot room.

Every time Rectenwald revisits that span of moments, his eyebrows prop up and his chin lifts into a smile.

* * *

He spoons through the Basmati rice, chewing some orangish-black chicken. The scurry and haste of Bollywood overhead. All around, the wooden scent of baked bread as it's pulled from the oven and buttered. I gawk at Rectenwald, “Are they saying my name?"

He laughs, then returns with a plate of sequined dessert, something that was boiled in milk then frozen into the shape of a pinecone. Every new plate feels like a surprise, something ordered by a stranger.

Between spoonfuls of rice, Rectenwald recalls the time Ginsberg was squeezing a harmonium and singing poems from Romantic poet William Blake's "Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience."

“At one point," he says, “I fell into a trance, during one of the songs, the one about the lamb. The little lamb. I had a religious experience."

We talk about Blake's "Marriage of Heaven and Hell," a strange collection of poems, full of disparity and contradiction. I tell Rectenwald that the Devil is loud in it and I always think of the line: “Without contraries is no progression."

He responds with the line: “Opposition is the best friendship."

“I feel like that's where we are as a culture, full of opposition," I say. Then I sigh journalistically, ask a high-minded question that's become a cliché: “So where do we go from here?"

“I think Glenn has a really great idea about how to fix it," he says. “That it has to be formalized, turned into a movement. Instead of a 'think tank,' how about a 'feeling tank'?"

“Bringing a sentimental element to it?" I ask.

“Yeah," he says. “Something that doesn't exclude the head, but it doesn't lead with it." He pauses to gnaw on a scatter of crumbs. “It's like Glenn and I talked about with Adam Smith's "Theory of Moral Sentiments." Moral sentiment first. That's what people forget. The father of capitalism first wrote a book about moral sentiment. That has to precede the marketplace, the establishment and maintenance of a marketplace, so that we begin from affect, from a place of charity, from and for each other."

I smile, nod, say something about life.

He replies that everything is political lately.

“It's coming from education," he adds. “It happens with education. You saw that in graduate school," he tells me, “I am confident of that, it was already starting to happen when you were there." He spoons in some glimmer of putty.

“I'm sure you saw how competitive the classroom was. Everybody's jockeying for a position with the professor. You learn which topics are going to be good for the market."

* * *

The man has been called some nasty things. In a multi-departmental email, a colleague repeatedly called him “SATAN." Although — as is often the case with people who REPEATEDLY emphasize words by capitalizing every letter — her opinion is somewhat unreliable, if not utterly insane.

In response to the Washington Square News article in 2016, a group of students, professors, and deans formed a 12-person committee called the Liberal Studies Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Working Group. They posted a letter to the editor. Below all the academic niceties they had a message: Rectenwald had been publicly mocking them and their ideas and their activism — and anonymously, no less — and they were pissed.

(It's important to add that, as a professor, Rectenwald appears to be overwhelmingly liked by his students, with a 4.5/5 rating on RateMyProf.)

Surprisingly, after coming out as @antipcNYUprof, Rectenwald received a promotion, but the work environment remained tense. On May 8, 2017, he boasted in a now-deleted tweet that he'd gotten a $75,000 advance to write a book about his fallout with academia.

In response, clinical assistant professor Terri Senft sent out a mass email through the NYU system to over 100 NYU staff, including Rectenwald. The subject line reads “Congrats to M. Rechtenwald on his 75K advance from St. Martin's Press!"

It starts with thinly-veiled sarcasm then bursts into full-throated activism. Reading it is like watching a gang of 4-year-olds fight in a full-sized-boxing ring, oversized gloves, shorts so big they look like a blanket. There's a recurring hint of valiance and grandiosity to many of the emails. Multiple times, people threaten to get human resources involved. Lawsuits are mentioned. Legalese is spoken. Character assassinations are made. Nearly every word bursts with anger and hostility. Years of pent-up rage spilling out over email.

Throughout the thread, Rectenwald's colleagues accuse him of being racist and sexist. They call him "alt-right." They call him a drug addict. They make judgments about his mental health and his character and who he is as a person. Nobody provides an example of Rectenwald actually acting racist or sexist or anything else, they just insist that he is.

They still have plenty of grievances, however. Assistant professor Jacqueline Bishop complains that, years ago, Rectenwald sent her an email asking for the password to her computer while she was out of town; she said no; then, she claims, Rectenwald sent an “abusive email."

Rectenwald disagrees and has repeatedly asked that Bishop release the alleged email but Bishop refuses to. Professor Carley Moore accuses him of “stare downs in the hallways." Someone accuses him of standing on a chair. Someone else accuses him of addressing them by the wrong title. Someone else claims that he bad-mouthed them to his “romantic partner."

At one point, Terri Senft writes that anyone who can't see that Rectenwald's “tactics" are caustic and dangerous should “re-read Foucault." Presumably, Senft is referring to the Foucaultian concept of power, particularly the abusive nature of institutional power — the idea that prisons, governments, courts, hospitals, and doctors and police and politicians, anybody or anything with authority, use power to assert dominance and maintain privilege — as well as Foucault's notions of discipline and punishment, and his assertion that the modern world is a patriarchal battleground governed by the Haves, who relentlessly and sadistically violate the Have-Nots. I can't say for sure, though, as professor Senft hasn't replied to my emails.

Of the 100-plus recipients of the email, only six people responded, and Michael Isaacson, known for his politics, was the only man besides Rectenwald to respond. He writes, directly to Rectenwald, “Sounds like you need a safe space, snowflake."

In one of his few responses to the thread, Rectenwald writes: “SJWs operate in pack and attack mobs. If you seek asylum from their baseless slander, libel, and defamation of character, they call you a 'snowflake,' imagining that they proffer a clever reversal."

But Bishop, an assistant professor, shows the most hostility toward Rectenwald.

“Lord, I cannot help but laugh about this," she writes. “I know this is serious stuff but it is soooo pathetic I have to laugh. … It is a pattern people and Michael Rectenwald is nothing but a COWARD and a BULLY and a total punk-ass. … People, there is NOTHING TO FEAR BUT FEAR ITSELF. … All smoke and mirrors, people. A total punk-ass."

He responded: “I consider any further contact from Jacqueline Bishop as harassment. No contact is acceptable."

Bishop disregarded Rectenwald's statement, sent several more emails. “My colleagues," she writes in one, “by Michael Rectenwald's own words we are dealing with a racist, sexist, misogynistic, adderal-filled bully. Take that to whom-ever you want to take that to you coward Michael Rectenwald. My colleagues if he tries to step to any one of you, all you need to do is step right back at him. DO NOT BE AFRAID. HE IS A COWARD AND A BULLY NOTHING MORE. SHOW HIM UP FROM THE FRAGILE WHITE MALE THAT HE IS. He comes after women of color and people he thinks has no power. NOT THIS TIME SATAN."

* * *

I ask, “What's the first novel that really impacted you?"

"The Stranger" by Camus, he tells me. A dark book, the kind you can read in an afternoon. But then you'll spend the next week shuddering, thinking about how there are no limits to Nothingness. A real funeral of a novel. (SPOILER ALERT) The guy's mom dies. He goes to the beach. Murders someone, some stranger. Gets convicted of murder. Doesn't fight it. Feels nothing. Never asks for forgiveness, doesn't ask for anything. Sentenced to death. Feels nothing. Then, somehow, to him, that nothingness signifies an awakening. His life takes meaning only when he imagines his execution in front of a crowd of hateful strangers. Book ends.

“I was about 16 or 17 when I read it," Rectenwald says. “It appealed to my feeling of always feeling — of always paying a price for independence. Personal independence. Intellectual independence. And the sense of alienation that [the main character] felt, socially and otherwise."

In the last stanza of his poem, “Via Topeka Kansas," Rectenwald writes, “This place is beginning to feel like my past. Somebody transported my being out here, while I was asleep. It seems like the autumn of my youth."

All around us, a gaudy, auto-tune pop song blares out lyrics in another language. If you muffle your ears it could be anything from anywhere. Someone is ramping a machine in the kitchen and it makes a high-pitched squeal like a leaf-blower. It's louder than the music, and it pecks with an annoying, unmusical pattern. As we get up, the metal underside of the table jerks over the floor and makes an awful groan. All this harsh sound is disorienting, and we struggle to find somewhere for the trash and the trays and the disposable cutlery.

“A lot of people liken my situation to [Camus'] "The Stranger," for some reason," Rectenwald says. “ I don't know why. For defying the herd, I guess. It's been said several times by several different people."

* * *

“When I was younger," Rectenwald says, “I liked Twain — Edgar Allen Poe. I loved Edgar Allen Poe. 'Tell-Tale Heart.'"

He wrote an essay about “The Tell-Tale Heart" as a high school freshman, and the teacher, a Jesuit priest, was convinced that it had been plagiarized. “He said it had way too much psychological insight," Rectenwald explains, then shrugs.

Rectenwald wrote poetry in the seminary. People liked it a lot. They told him to keep writing. “I wasn't any good yet," he says. “I showed promise, I guess."

When he mentions writing poetry in the seminary, I ask about Gerard Manley Hopkins, a fairly obscure Victorian poet. I tell Rectenwald that when you read Hopkins aloud, it sounds like hip-hop — which is a hell of an accomplishment for a Jesuit priest from the 19th century who wrote poems about grass, birds, and shipwrecks.

I ask Rectenwald, “What's your favorite Hopkins poem?"

“The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo."

It's my favorite as well. Hopkins said of the poem, “I never did anything more musical." Leaden echo: bad, and everything bad, like dark and evil. Golden echo: good, and everything good, like light and Jesus. The poem fulminates with a separateness brought together. Two parts, identical yet opposite, mirrored echoes of each other becoming their own mirrored echoes, whose answer is the opposite of the original. It's the fight between life and death, youth and age, God and the Devil, Heaven and Hell, All and nothingness. It's a hell of a poem. Colin Farrell recited it at actress Elizabeth Taylor's funeral.

Here are a few lines:

Undone, done with, soon done with, and yet dearly and dangerously sweet

Of us, the wimpled-water-dimpled, not-by-morning-matchèd face,

The flower of beauty, fleece of beauty, too too apt to, ah! to fleet,

Never fleets móre, fastened with the tenderest truth

To its own best being and its loveliness of youth: it is an everlastingness of, O it is an all youth!

“Beautiful language," Rectenwald says with a gust. “Hopkins was a language master. And, yes, musical. It's musical."

We shove the door outward and, outside, the heat is immediate. The freeway traffic hums a static sound, like the shuffling fuzz as a needle falls onto an LP and the speakers are up loud. Dallas/Fort Worth Airport is a 10-minute car ride away, so the sky wiggles with stiff white missiles floating in every direction.

* * *

“So who would you be," I ask, “if you were a character in a book?"

“Alton Locke," he says. “Written by — hm. It's a 19 th Century novel. By. What's his name?" He fumbles around for it. Then gives up and pads his pocket for his phone. Outside the 7-Eleven, two different landscape crews lean against trees, swatting at flies and chugging Gatorade in the shade. Traffic has gotten busier in the past half-hour.

“Where are we going from here?" he asks, distracted by his phone.

“Around this corner," I say, “then we'll cross — and make sure we don't get run over, ha ha."

I scope the road and wait for the WALK sign. Drivers here don't give a damn about other drivers, let alone non-drivers. I pace out at the precise moment, and assume that Rectenwald is following. No way to explain it if I took the man to lunch and he got run over by a semitruck.

* * *

When I turn around, Rectenwald is standing in the middle of the road, staring down at his phone. I want to tell him that we can find out who the author is later, then I realize he's asking Siri a question.

“What happened to Mac? What happened to Mac?"

He plods tip-toe steps all the way across the road and, in this Texas heat, in this chaos, I will confess that I feel like a mother duck trying to shepherd so many ducklings across a freeway. The road quakes with the weight of trucks — trucks that, in New York City, would be part of some industrial company but, here in Texas, those are just trucks. And not even particularly big ones. Texas has gigantic trucks like the hidden depths of the Amazon has gigantic spiders.

“By God, lad, hurry," I mutter to myself, chewing at my lip. “These bloody drivers see us as a speed bump."

As soon as his feet plant into the grass, safely across the street, I exhale deeply enough that I feel physically lighter. But there's a sudden emptiness in the air and I feel awkward and just spit out a meaningless question: “So you're only here for the day, huh?"

“Mac," he's saying. “Siri, tell me about Mac." He turns to me, a bit dazed, “Something terrible happened to Mac."

“Mac Miller? The rapper?" I ask, a little confused.

“Yeah, yeah. You know him? My son is signed to his label: Remember Music. He's the greatest guy you could ever meet. We're close with his family."

“What happened to Mac?" he whispers to himself.

He turns back to his phone. “What happened to Mac Miller?" He repeats the question, a little louder each time. Siri responds with something about an email or a retired basketball player. “No, no — What happened to Mac Miller."

We stand at the bump of grass at the edge of the parking lot. From here, the studio looks like a gateway.

Rectenwald gasps: “He's dead!"

His face collapses.

He gasps.

He grunts a series of primitive noises.

“He died."

He heaves out air so hard that his mouth flubs and claps and he starts pacing around a grey Kia Optima with a stupid bumper sticker.

“What?" he says.

My first thought is that the passing cars need to be quieter, more respectful of the dead.

“Oh my God," he says.

He heaves leftward, then looks for a place. He wants to be alone. And I turn and walk toward the studios and slump onto the curb and stare straight ahead. Dead means gone forever, and gone forever means something we can't comprehend. Rectenwald's poem “The Finish Line" ends with the line: “Thank God for poetry to speak of the endless unnamed." And he's cramped into the hidden quiet between two black SUVs. Nobody else is around. Nobody, only drivers passing. I can hear him. Stare ahead. Neat white lines are parking spaces.

After a minute and a half, he walks toward me, apologizing.

I apologize back.

Right there, in the parking lot, in the heat and the shade and the commotion of traffic, I give him a hug.

“This kid was my son's best friend..." mumbling, “...just beat Stage 4 cancer and this kid was there every second," mumbling, then declarative: “This is so wrong."

He looks away for a second, then back down at his phone.

He gasps again. It has started all over again. “He died of an overdose." This news is as destructive as the original news.

“I gotta call my son," he says.

I say “yeah" and “sorry."

He stalls in front of Building Two, beneath the metal stairway. The walls are beige. Sometimes people smoke in the doorways, but mostly there's no one. The grass has a smacking, photoshopped green to it. All of the parking lot is covered by shade, because the trees are big like giant umbrellas. Nobody else walks around outside. Just me and this professor from NYU who's mourning the death of a 26-year-old rapper who dated Arianna Grande and presumably overdosed on heroin of some kind. But he's far more than that to Michael Rectenwald.

And it's an odd feeling to simultaneously know and not know the person who someone you've just met, but whose writing you know well, is mourning. Freshly tarred, the road stinks like plastic melting in a fire.

Two minutes later, Rectenwald lumbers back. He apologizes again but I tell him no. We nod. Then he says, “Let's get inside, I'm fucking sweltering."

We exchange the phrases that people exchange in such circumstances. Our apologies are far more than apologies. With each “sorry," we're facing a world that will always move fast. “Sorry" means that for all our love of words, sometimes there's nothing you could say that would mean what you need it to mean, and that's too much to deal with, so just say “sorry" and deal with this other thing, the thing that leaves you wordless when it happens.

“Tragic," he says.

“Tragic," I say.

“This fucking disease, man."

“It's a fucking disease, man." I can hear how it sounds, like a kid swearing for the first time, but the point is what will help?

The remaining 60 yards throb with a heavy silence. Nothing to say. Nothing that could be heard over the raw emotions of the moment. Why not? Nothing to say. Say it. Say what? Nothing to say. It's 4 p.m. on a Friday and a storm is coming and there's nothing to say.

We pace up the ramp to the backstage entrance. I pause for a moment before opening the door.

“You ready?" I ask. I'm asking him if he's ready, but let's all admit that, really, I'm asking myself if I'm ready because I know very little about being ready at this moment!

Inside, the studio is cold and I hand Rectenwald a bottle of water. He starts to sit down at the first couch he sees: That loopy neon green one, the Austin Powers lava-lamp sofa. Somehow, it feels disrespectful to let him mourn on such a cartoonish thing, so I wave him to a more dignified seating arrangement.

As soon as he leans back, I realize that he's sitting at the center of everything. Most of the studio's interior walls are glass, so everybody can see him. I run to my desk for a moment to grab my laptop, then linger there a moment, staring at the copy of Don DeLillo's Underworld next to my phone.

When I look up, Rectenwald is gone, the water bottle unopened and pathetic like a turd on the ground. I pick it up and take it to the guest dressing-room. He's sitting upright in a bright-red nylon chair, in a room full of mirrors.

I bet if you find the right angle, the mirrors will make an echo effect — an infinite number of Rectenwalds past an infinite number of you.

JIM WATSON / Contributor | Getty Images

JIM WATSON / Contributor | Getty Images

Joe Raedle / Staff | Getty Images

Joe Raedle / Staff | Getty Images AASHISH KIPHAYET / Contributor | Getty Images

AASHISH KIPHAYET / Contributor | Getty Images Harold M. Lambert / Contributor | Getty Images

Harold M. Lambert / Contributor | Getty Images